|

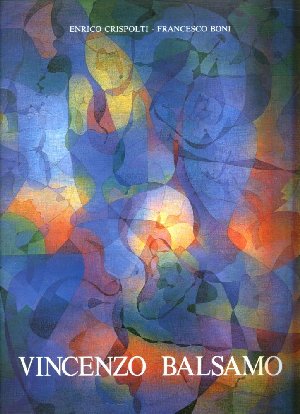

This monography, of 216 pages published in year 1992, it contains a series of essays that have been published

in the previous years. The essays have stayed brought again following the exact chronological order of printing, you could

read them choosing the Critic that takes an interest mostly.

Renato Torti

Enrico Crispolti

Francesco Boni

Gigi Montini

Enrico Contardi-Rhodio

Giovanni Omiccioli

Angelo Zizzari

Sergio Rossi

Enzo Di Martino

Marcello Venturoli

Michele Calabrese

RENATO TORTI

A letter to a friend

Dear Enzo,

the occasion of your anthological exhibition, underlined by a monograph on your long career as an artist,

written by one of our best critics, fills me with the nostalgia of distant memories, always present to me.

We mwt by chance in the middle of the 1950s at Brandi's, the frame-maker and craftsman of Trastevere, where we had

brought our pictures. You were little more than a boy, just arrived in Rome from your hometown, Brindisi and you already

conquered - it was simple, it was possible, then - a luminous studio overlooking the plane trees of Lungotevere degli

Artigiani. It was just walking along the Tiber - we were so young, and I a little older than you - without much money but

rich in dreams, we met the first important people of our life: Renzo Vespignani, Antonio Vangelli, Ugo Attardi... who, like

us, stayed up late looking for inspiration. It was still a naive country, Italy, with the open wounds of the post-war period,

but already rich in cultural ideas, for example, painting 'en plain air' on the Roman outskirts. From those walks came the

first ideas for landascapes which are now in the history of Italian painting. And which had been earlier 'landscape of the

soul' the gasometer, the bridges on the river, the trellis of Purfina.

Then the 1960s came and Trastevere, so authentic, so untouched, became the Roman Montparnasse, much better than

the sophisticated, conventional elegance of Via Margutta and Via del Babuino which attracted the curiosity of foreign

tourists. The 'real Rome' found its shelter there, the artists chose it as their citadel, transforming its streets into a sort of

'moveable feast' of creative pulsions and chromatic emotions.

A young man, a crazy, reckless talent, Angelo Zizzari, after a short apprenticeship at Brandi's, without a lira, opened the

'Bottega', in Piazza Gioachino Belli, which we proudly defined the first art gallery in that area but which was only a

workshop for frames (this was needed for his survival); it made us artists - we were all poor - very happy because we

had found a public nail to hang our pictures on. Angelo was 'a man of the night' and as it fatally happenes in creative and

unpretentious years the 'Bottega' slowly became the aggregation point for an extraordinary slice of mankind:

watermelon sellers, carters, idlers, innkeepers, whores who constituted the real essence of 'romanità'. There we played

cards, drank wine and 'were doing art'.

How sweet, romantic, eccentric those years were; when the evening arrived, we saw the likes of Luigi Bartolini, Carlo

Levi, Ugo Moretti, Mario Russo, Sante Monachesi, Toto Vangelli, Pie Paolo Pasolini who caught there so many

intuitions for memorable pages on the despairing mankind of the outskirts. Sandro Penna was there, too and looking at

the public toilet in front of the shop, he wrote the famous 'forbidden' poem: "The handsome boy is coming out of the

public toilet...". And then the great Mario Mafai who, talking with us, decided to paint, as an interlude for his red-hot

landscapes and dead flowers the fascinating series of the 'brothels', in decadent slendour. Talking about that, how can I

forget the exhibition he organized at the Bottega and which it would be impossible to do now, not only for its

completeness and quality, but also for the enormous costs it would require. Well, Angelo Zizzari, who should have been

the custodian, went after a woman and so the gallery was left open with its treasures, protected only by the affectionate

but occasional attention of the neighbours. It was our way to be young. And free. "Sorcerer's apprentices", I, you,

Giuseppe Bartolini, Carlo Quattrucci, Gilberto Filibeck, Enzo Tilia, Rodolfo Guglielmi, Salvatore Provino, the Antonaci

brothers - we watched in enchantment the exhibitions at the Bottega and the daily discussions of the 'masters'. These

often ended up in violent quarrels which looked like irrimediable breaks: the day after, it was peace again, as if nothing

had happened. Extraordinary lessons of life and art, for us.

The passing of the years and the arrival of easy money made society and our world more vulgar and gave our ideas a

bourgeois turn. The naive Roman bohéme dissolved and the friends separated. Some of us met seccess while still

alive. For some others it came too late. But historical memory shows that each of them has been a fundamental

presence in the Italian cultural panorama of our century.

Now it's up to you. And success maybe is a negligible thing for one like you with this experience of life and tenacious

devotion to art.

What else can I say? Remember that my wishes this time, and always, have something more: thirty-five uninterrupted years of trust, complicity, love.

Genzano di Roma, August 1992, RENATO TORTI

Top

Enrico Crispolti

MONITORING FANTASTIC PHYSIOLOGY

Enzo Di Martino was certainly right when he wrote, a couple of years ago: "Balsamo's 'expressive project' does not

consist in fixing static images on the surface of a painting; it wants to chase the 'forming lines' which continually interlace

and break up in reality in an open, endless process". However, the chase takes place on a dimension which is elastic

but is anyway a surface, as if it were a revealing screen where we can observe, as in a sort of monitor, the forms

interlacing and breaking up, in their evidence of meaningful, formal pictorial construction, in a condition of substantial

motility.

Since the middle of the 1980 Balsamo's pictures have been based on costant foundations. On the surface, which is

elastic but actually insurmountable in the meaningful plotting which formally and chromatically constitutes it, giving it a

frontal dimension, and which can be surmounted only as development in space, mentally imaginable rather than visually

perceptible, a mobile, dancing plot, or better embedding, appears: it is made of formal shapes, characterised by their

supple linear profile, curvilinear but which is sometimes exalted towards the clerification of evocative symbolic primary

hints, whose function is to determine the meaning of the image which the plot or embedding of shapes inevitably

assumes. This is not ubiquitously expanded on the whole surface but softly oriented towards the centrality of the event

which is both formally and chromatically the protagonist if the scenic fiels, given by the weft, tissularly uniform to the

surface itself.

The surface, on its turn, is not seen as compact bottom but as detailed, orthogonal, chromatic weft, able to offer to the

very strcture of the protagonist image the basic colouristic intonation, getting lighter, or darker or red, but also becoming

the internal body of the formal shapes graphically dafined in their changeable profiles. Above all, it generates, through

the chromatic quality of the signs, the endogenous brightness which the variable (even if, from time to time, tuned in a

rather univocal way) chromatic quality of the orthogonal plot exalts and transfers to the formal shapes, offering them the

texture of internal consistency.

This tipology of the foundations of his work gives Balsamo's pictures the quality of the proposition, aggregative process,

substantially an open one, continually reformulated, even if in analogous, clearly seen directions. We are then offered

the place of a frontally formalized image, the winking cadence of a confidently organic analogy, and exactly a possible

space in memory, which is collective in its hints, not inclined towards individual research. A dimension of memory which

is completely, so to speak, decanted, separated from every fortuitous referential definition and pushed forward as in a

sort of hinting inventory of the possible archetypes of assumed basic naturalness, obtained through lyricism but also

playfully. This happens without any primitivist displacement, on the contrary through their decided formal acculturation

creating fables, and their recitative designation, almost a routine, but never extinguishing the happy freshness of

authentic evocative invention.

Actually, Balsamo, more than a space of memories, specifically suggests a space, or better a screen of the activities of

memory, as the well ordered and not unforeseeable manifestation of possible lyrically evocative activity, as a fantastic,

spontaneous process, and a natural one, therefore continually reoffered as the vital imaginative flux appearing from time

to time in new combinations. Space or screen of memory as the field of manifestation, recovery and reproposal of the

imaginative activity which is anthropologically necessary, therefore of a fiels of activity which is specifically poetic,

brought back to its sources against the referential, detailed description of further narrative developments. We could

difine it as the institution of a contact with the inexhaustible flux-which for Balsamo is somehow intransgressible-of

lyrical, fantastic evocation as structural activity, anthropologivally vital.

It is not then imagination freely evoking but, we could almost say, evocation of daydreaming: it is directed combinatorily

to the construction of a sort of phenomenology of fabulous possibilities within a basic language of signs using

elementary-but at the time sophisticated - hints referring to eventful plots (as the well defined result of the motility of

costant ingredients).

Also, a sort of formalized objectivation of something as conscious oneiric activity, scenically using the process of

aggregation and automatic development, but within the limits of a precise, unbreakable 'expressive project' bearing

witness to unbroken activity . continually reproposed in its constitutive elements - of imagining the 'forming lines' of

formal-graphical combinations whose foreseen unforeseeability outlines, as if on a monitor screen, the rhytmic

physiology of the pulse of a vitally imaginative activity, which is necessary both for the artist and the person who

contemplates his work and is offered such testimony.

Hence the constant analogy of principle in Balsamo's pictures, since the middle of the 1980s: it has been stubbornly

chased and somehow guaranteed, in an inventory of possible results, predictably endless. It is continuos, conscious

reinvention we are talking about, certanly not repetition, that would be even statistically not provable. In fact, Balsamo

monitors microscopically the formal processes of a sort of fantastic physiology, reinventing every time the chromatic set

which characterises its intonation.

Some critics have talked of his debt towards Klee, not a literal one, but seen as a basic introspective option. In fact, if

we examine the level of signs and formal solutions, the most relevant suggestions seem to come from Mirò (in some

particular cases from Kandinskji in his mature years). But Balsamo's phenomenology of pictorial work doesn't share

with Klee the formative principle, unconditionally genetic; on the contrary it asserts the rights of an elementary formal

combinatory principle, all of his own.

I believe however that Balsamo owes something to Mirò's lesson: in particular the represented extroversion of detailed

formal descriptions with their symbolic hints which characterise all the images he has given us. On the other hand, these

are devoid of poetic mystery and cherged with evocative allusiviness which has a foundation more natural than psychic

(Vito Apuleo in a 1990 text recalls "the flight of a butterfly, the whims of the clouds, the thread which the baby's hand

holds while anxiously watching the movements of his multicoloured kite"; and similarly De Martino talks "a face, a

microorganism, a kite". These 'forming lines' constituite on the surface - plotted with signs in a very regular way and

luminously activating the endogenous potentialities of a 'display', a pictorial one in this case - from time to time the

unrepeated phenomenology of possible narrative itineraries, which are equivalent to the revelation of the

microprocesses in motion of an imaginative physiology, chancing colour every time according to different possible

cadences of humour, evocative, joyful or mediative, sometimes even almost dramatic.

Balsamo's pictures are not then pages from a diary, an accidental, chnce diary, of course, but, I would like to say,

something as prearranged graphical-formal performances, at the same time consciously improvised: a sort of free but

also oriented music derived from free jazz, creating a sound which is rather predictable but always different and

surprising. Those 'forming lines' constantly interlace their narrative events in a sort of mental biomorphism, episodes

from an inexhausted tale, taken to its extreme towards an imaginative formal synthesis; this is part of the nature of

testimony, present in all of Balsamo's paintings of the existence of naturalness of fantastic activity which he can catch in

his private interior hearing and which he propoes, iconically ordered, as the index of a possible imaginative

displacement, lyrically rewarding, which can be shared by his reader. In this tale, inside the basic humoral intonation

chromatically determined by the colour quality of the underlying plot of signs, he is able to develop different suggestions,

not necessarily, it seems to me, with lyrical, sentimental, evocative references but with allusive combinations (but they

also can be found in an inventory) inside which we can observe the work of subtle irony. Widw itineraries of linear

interlaced profiles which, if they penetrate the formal hints, substantially biomorphic ones, are then detailed in episodes

with a sharper outline, decisive under the narrative profile. These are itineraries which clearly Balsamo determines

using functionally a process os automatic invention, giving however this other margin only the combinatory formal

freedom, in order to obtain a scenical, choral proposition of the aggregation ot the image, eventually solved in the

thickening of the dislayed formal plot, detailed in decisive occasions of symbolic allusiveness. Hence the appearance of

"unspeakable self-sufficiency" that the paintings of Balsamo's latest phase (which has been going on for quite a long

period of time now) constantly and stubbornly show. I think De Martino is right, once more, when he advises us:

"Paradoxically, the possibility of 'reading' Vincenzo Balsamo's work does not exist; we only have the chance of 'losing

ourselves in its contemplation'".

About 1985 Balsamo's research reached the structuration on which it has consolidated in the subsequent yaers, and up

to now: drawn plots, interpenetration of the shapes of evoked images. Just before that there had been the meeting, a

decisive one, I believe, for his future orientation, with Klee's introspective formal universe. He had got there through his

work on the dialectical composition of formal shapes, sufficiently compact in their chromatic principles, expanded on the

surface . This happened in the early 1980s, specifically underlining the final conquest of a space in memory, an

evocative one, which had begun to appear in Balsamo's research at the end of the 1970s (about 1978): to be precise, it

was a particular and rather irregular experience of indirect marks (from ropes, above all) inside a pictorial texture

entirely based on the use of the spray gun (without any effective relationship with Cagli's experiences, which are only

instrumentally similar) resulting in hints of images, signs etc. inside an implicit spatiality in reference to memory.

If the experience of the early 1980s with its pagination interpenetrated with forms to create evident images offered an

archetype of the modality of the composition's framework to subsequent paintings, where, however, the formal entities

were graphically lightened, giving up the task of their chromatic substantation to the basic plot and its signs and colours,

nonetheless a distant but significant precedent - indicating the willingness to identify the substance of the pictorial

surface with the graphic plot, in a phase of Balsamo's research which was still esperimental - had appeared, in a still

earlier period, precisely in the 1977 group of paintings, based on the pulverization of microsigns on the entire surface,

singling out subtle itineraries and tangles. These experiences were leading to the decisive maturity of his work,

beginning with the middle of the 1980s.

Remote but significant premonition, one for the definition of the mentality necessary foe the composition's framework,

the other for the tissular attention which constitutes the actual pictorial surface. In the middle of the 1970s Balsamo had

reached the phase of non-figurative propositions, creating pure formal entities, predominantly curvilinear in their

profiles, completely laying them on a plane (he titled them Abstract Composition and numbered them). Behind him he

had fifteen years of figurative painting, which had shown, at the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s, some

'roman' link, in his cursive practice (especially portraits), chromatically tapered in its local attention but still in a vague

contact with tonal culture. Then he was an expressionist in other portraits and in the landscapes (some of them Tuscan)

of the early 1970s and beyond, up to the square still lives, more carefully constructed chromatically standing out even in

wide, almost deliberately rough drafts (about 1967). Almost a 'neo-fauve', but with more care, in others between 1968

and 1970, while in his syntetic landscapes he relied more freely on the constructivity of colour (maybe with some

suggestion from Mafai's last figurative phase). At the beginning of the 1970s the framework given by postcubist

synthesis provided him with a landingplace on the plane in still lives (1972 and 1973), with flat areas, curvilinearly

encircled, and with rather rough, very bright colours. This is the presupposition for the non-figurative solution which

appears in his work in 1974, almost in 'concrete' terms, of a pure formal framework, constituting the compact image

standing out on the background. The image is built through the interpenetration of formal elements, its chromatism is

very bright, but there are still some inflexions of the tonal echo.

But these are still experimental years for Balsamo: in 1976 he suggests a scattered definition, through signs and matter,

of the entire surface, up to some black matter paintings, very suggestive, whose title is "Decomposition": there is some

evident attention towards Burri's early metter paintings. Surface made of matter, uniformly black, where fragments of

objects or matter, again, emerge. A very interesting moment in Balsamo's work, even if a bit unrelated to the itineraries

of recent research; unless we want to see in that an exercise in the possession of the entire surface and a test of the

scattering of the most signifacant signs. The sudsequent year we have the pulverization of microsigns, always on the

entire surface, and 1978 the experiments of surface with the spray gun: indirect marks, hints of image signs etc. and the

conquest of a dimension of geometry.

We finally get to the experiences of the early 1980s, the trace of the constitutive combinatory modality based on plot and

embedding leading to the better known tipology of Balsamo's work, since the middle of the 1980s, whose original

characteristic we have tried to illustrate.

I met for the first time on the walls of a stand in The Arte Roma exhibition. I was impressed by evident margin of their

singularity, even if within a framework of apparent decorative challenge. But reading Balsamo's pictorial texts in a

decorative way means not to understand substantially the sense of their irreproachable inventive variety of experience,

singled out and not repeated within a constant modality of presentation. We can consider this as the choice of a

tipology of controlled and ordered monitoring of unrepeated manifestations of fantastic physiology, subtly allusive,

fabulously poetic. These are not variation of the same formal framework; they are the continuous, stubborn reinvention of

possible monitored itineraries, the iconic signs of his imagination, captiously evocative in its own way.

Rome, June 1992, ENRICO CRISPOLTI

Top

Francesco Boni

BALSAMO, AESTHETICS AND POETICS,

THE SUGGESTIVE LANGUAGE OF LIFE AND POTRY

Almost five centuries have passed since Leonardo wrote: "Experience, the mother of all certanties"; in his time the

illusion of certainy was still possible, while nowadays everyone who has some artistic experience, some knowledge of

the creators of culture and is in the abit of meditating upon the things he has done, studied, thought or written knows

that arts and sciences may advance only in the conscience of their own uncertainty. The great philosophies of our time

(Existentialism up to Heidegger, Oxford analytical school, Frankfurt school) the structural, linguistic, communicative,

psychological, political, anthropological analyses are stammering. In the field of science every year a new theoretical

hypothesis refures the wonders of the previous formulations. The first uncertain, uneasy steps of the astronaut -

impressed on our visual memory-become the symbolic image of our self, of man, at the beginning of the new era we

are going to live in: this is the moment when the new world becomes enchantedly wonderful because it is to discover.

Vincenzo Balsamo's artistic activity is perfectly inserted in this phase of thought, because it finds its reasons in the

theoretical conscience of the past and in the observation of the uncertainty of the future, to eventually explode in a

painting of action which is exalted in the discovery of a new, always changing reality. The barriers Pavese loved to

place between the known land and the one to be discovered have collapsed, our assuptions are more and more

uncertain. Only one thing is absolutely real, perenially young, always in the avant-grade: art. A prehistoric graffito, a

protogeomatrical vase, an egyptian fresco, a window in Chartres, the works of Giotto, Masaccio, Piero Della

Francesca, Giovanni Ballini, Raffaello, Tiziano, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, De

Chirico, Pollock, Warhol, Festa, I am leaving the living ones out, have one thing in common, they are absolutely real,

they are obsolutely beautiful, in the sense that nothing in them is improvable, notjing in them is not valid anymore, while

the sciences which were assumed to be based on reality, on logic, on verifiability, are continually refuted. This

introduction about the eternal youth of art and the progressive decline of scientific notions, if one believes them to be

unchangeable, was necessary before talking about the objectives, the working methods and the results obtained by an

artist like Balsamo who is the point of arrival of what I have been saying, if we interpret him historically and the starting

point in the declaration of the creative doubt; I also want to talk about the very close relationship between aesthetics

and poetics in him.

Aesthetics in the discipline which deals with beauty and art as seen from outside, poetics is the discepline which

deals with them as seen from 'inside'; the first is the domain of philosophers and critics, the second of the artists; the

first is an instrument of knowledge, the second of work. In Italian culture aesthetics normally tends to establish the

relationship of art with the structure of communication, either including or excluding it or, which happens more often,

putting it aside. All these are vague, strange theories if compared with the scientific ones, Actually, a technical product

is always the exact result of some scientific theories while a work of art anly partially respects the poetic theory which

forms it. If it reflected the theory faithfully it would be reduced to an illustration of that teory and so would lose all its

validity as a work of art.

Balsamo is perfectly aware of all this and, quoting Gide he correctly maintains that is, the theory of an artist, his

poetics, is born as a meditation on the new work which has just been done and partially as a project for the one to be

done. If an artist, when he begins his new work 'uses' a theory, be it 'his' or anybody else's, he surely is a mediocre

painter, maybe an academician, certainly nothing more than an illustrator; of course he must take theories into

account, but only partially, aware of the fact that the essential elements will come from inside, from his constant

creative ability which distinguishes him from any other living being. That is the reason why Balsamo paints, the need to

do, the need to express himself through sign, perfectly aware that all theories are temporary, non-dogmatic, something

to believe and not to believe in at the same time.

There is a question now which Balsamo ask, and we with him: how can art remain valid while the poetics which were

behind it have partially declined? Almost nothing of Piero or Leonardo's theories survives, except from a historical

point of view, and we can't use much of Kandinskji, Malevic, Mondrian or Seurat's theories, today, and despite his

vast, intelligent work as a teacher, not a single great artist was formed at Klee's school. This is yet another

demonstration that from theorical knowledge only a mannered painter can be born, in the best case a very talented

one like Tintoretto who wanted to combine Michelangelo's technique of drawing and Tiziano's technique of colour.

Actually art infinitly exceeds any form of theory and lives in the practice, in the creation of every artist who paints with

authentic inspiration and is able to show his autonomous 'self' through his complete control over technical instruments.

Balsamo is perfectly aware that the only real improvements an artist can obtain, after the phase of ispiration, lie in his

mastering of technique acquired through work, study and above all active experience. Only in this phase tha artist has

the greatest liberty and he can tell advance from easy tricks, the ones done only to try something new. It is easy to

mistake 'style' for 'originality'. Style is a difficult conquest, it doesn't eliminate the past, it goes beyond it, originality can

he mistaken for fashion, it does not advance, it only varies, and often it is result more of a theoretical project than of

intuiton and this is probably why our world based on mass consumption likes it so much. Balsamo is a painter and a

man of our time and he has lived these problems in first person, and he has interiorized them until he has been able to

show an autonomous conscience. When we write about painting and specifically about this kind of problems and

questions, which are the essence of Balsamo as a painter, the things we say can be different and all justifiable, the

only thing which it would be impossible to say is that his art doesn't provoke 'debate'; it does, because it proposes

fundamental elements in the artistic debate. It is certain that his painting can be considered absolutely 'different' from

the painting which is now celebrated in fashionable salons and at the same time, his expression, so intense and lively,

extraordinarily full of substance, ideas, intelligent links between the past and the present, is totally inseparable from the

conscience of our sensibility. Painting then which is sincerely rooted in the 'feeling' for the past, even if it derives,

through the filtre of a sharp, expert sensibility, from the present circumstances of existence, which are maybe eternal.

Maybe this is the reason why his images, his statement which is at the same time spontaneous and meditative, his

way to conceive painting, fresh and thoughtful, provoke 'debate' and appear totally 'different', maybe 'out of place' in

comparison with the great majority of present yime painting. The reason for this is that Balsamo doesn't paint because

he likes to be liked, and even less he wants success fot its own sake; his anxiety to communicate and also the

circumstances of his career, the public destiny of his work and his research, are entrusted to a different rigour, more

intimate jealous and secret, as it has always happened and still happens with every true, authentic artist, in every age

and culture.

They are entrusted, that is, to the solid poetic substance of the image, that wonderful, yearning balance between

deftness and intuition, creativity and fullness of feeling which distinguishes the work of a real artist. And they also feed

on a deep pictorial culture, on the loving, careful glance towards some great masters of our recent past whom

Balsamo, a precocious artist, has always admired, in a relationship with their works which has never been bookish or

notional. A relationship (very far away from the deliberate use of 'quotations' typical of some of the present vacuous

discoverers of painting) which has been deeply present in his images and in their crackling tactility, giving their

contribution to the definition of the peculiar, unrepeatable flavour of their charm, of their penetrating ability to create

suggestion. The miracle consists in creating such subtle, new balance, but not letting this act become abuse, a mere

operation of language, that is the result of a programmatic stylistic project, and as such emphasized. On the contrary,

the interwining of colours and space, the luminous impressions and their connections, the rhythms of composition, the

solid pigments, flow and are defined from the author's imagination to the surface of the painting, always with

extraordinary naturalness, in the fullness of a voice which is now mature. We can say, in a certain sense that

Balsamo's secret fascination is exactly here, in the ancient heart of his chromatic enunciation, in his roots of poetics

and sensibilities, rediscovered and given new life on the basis of the colouristic and intellectual experiences of our

century. Art is never for its own sake in Balsamo, it is not consumed in mere aestheticism; it becomes the pulsating

fruit of throught and action, translated by the artist into a sign as the synthetis of a poetic relationship between things

and our existence.

Art doesn't have fixed times or places, it lives in its interior 'duration', it has a basic form of morality which constantly

appears on the surface and is reformed in all circumstances of human reality. That's why Balsamo's operating terms

live together, new and amcient at the same time, deeply autonomous but also integral part of a sedimentation of the

continuity of an itinerary which started a long way off. Yet, the present time strongly lives in its 'connections' - in fact, it is

their barycentre, the permanent reference of insipiration, a reality which is not only objective but is rather the synthesis

of our interior life. It's the present time living in the mind, made of domestic, daily things; the ability to write in a diary

the effects and emotions of a single day, as the small events which punctuate the author's life in his contact with the

world we live in and which we can find in the fears and anxieties we feel as men of this century. Above all, this present

time, this topicality is able, thanks to an intimate poetic virtue, to accept large mataphors, complex echoes, general

feelings. So the rooms and the objects, the family, the moments of the day, the usual places of existence become a

pretext to reflect and revisit autobiographically one's life and, at the same time, they develop into traces of a practice

and expression of an existence emotionally aware of universal complexity.

So, effections and worrie, memories, warnings, dreams and abandons quietly circulating among these signs and

colours in their tender conscious lyrical solidity, always speak for those who can lend an ear to an intense, vibrant,

suggestive language of life and poetry.

Fiuggi, 2 settembre 1992, FRANCESCO BONI

Top

| |